Newsletter Archive (2011-2021)/Newsletters/Drafts

Better photography

There are a lot of things you can do to improve your photography, but one of the first options is to get good equipment. With the Small Grants scheme in full swing, it seems like a good time to cover some basics of choosing a camera.

Film vs digital

I love film, and I've been spending a lot of time taking photos with my growing (much to my wife's annoyance) collection of old cameras. Although many may be surprised by this, film isn't quite dead. In particular, the 35mm and 120mm formats are still available, and cameras that use both are both common and relatively cheap. Scanners are not too expensive, either, so it is not too hard to convert the negatives to digital. That said, it is a complex process - you need to develop the film, scan it in and clean it up in photoshop, and while the quality can be quite high, it is faster, easier and cheaper to use digital. Thus it should come as no surprise that most of us will choose to use digital - it is quick, easy, provides high-quality results, and allows photographers to preview their photos on the spot. And, most importantly, it allows you to take dozens of photos of a scene, trying different things, while with film you may only be able to afford one or two. The speed does come at the cost of careful composition, which you are forced to do with film, but the ability to experiment counters this neatly. That said, if you only have film-based equipment, or have a collection of negatives or prints, scanning in images can produce high quality output that could be of immense value to the community.

Sensor size

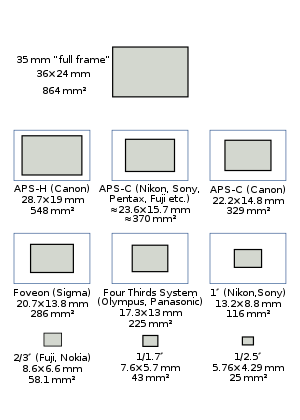

So let's look at the digital option. There are a number of factors which influence the potential quality of digital shots, and the first of these is the sensor. The first factor to consider is size. As a general rule, the larger the sensor, the clearer and less noisy the photos. A larger sensor means that you can have a lower pixel density, but still have the same number of pixels overall, so the pixels can be spread out over a larger area. A camera phone will have a tiny little sensor, and therefore will generally perform badly in low light conditions, and will lack the clarity of a larger sensor. Point-and-shoot cameras tend to have larger sensors (typically around 25mm2), and digital SLRs have a sensor of around 370mm2. After that you start to hit professional-grade cameras, with "full frame" sensors (the same size as 35mm film, or 864mm2), and medium format sensors (up to 1977mm2).

Another factor is the sensor speed. In the film days you used to purchase films with different ISO ratings. A "fast" film, like an 800 ISO, was good in low light conditions or when going for action shots, as it didn't need as much light to take a photo, and therefore you could use faster shutter speeds to capture the action. However, the trade off was more grain in the picture. A slower film, such as 100 ISO, gave a clearer photo, but needed either more light or slower shutter speeds. The same general rule applies to digital sensors. Sensors can be fast (up to the equivalent of 6400 ISO), and they can also be slow (typically down to 100 ISO). When set to be slow the picture will be clearer, but may be limited to good light with relatively static subjects; and when set to a fast ISO you can capture action, but the photo will have more noise. Thus a consideration when selecting a camera is what the ISO range is like - is it too noisy to be useful at 800 ISO? Or can you push that up to 1600 or 3200 ISO and still get an acceptable picture?

Lenses

Back when I started photography, I was told to pick my lenses and then choose a camera body to match. The camera body was, after all, primarily a light-proof box with a shutter. The real work was done by the lens. These days things aren't so simple, as the body is far more than just a box, but the lens is still essential.

With this in mind, your first choice is between a camera that has a zoom lens and one that uses a fixed focal length, often referred to as a "prime lens". Zoom lens are extremely convenient. You can zoom in or out to compose the shot without having to move from the spot. With fixed focal lengths you need to physically move closer or further away, and sometimes you just won't be able to achieve what you want to. On the other hand, from a design perspective it is generally much easier to make a good fixed focus lens - they are faster and sharper than their zoom equivalents. This is especially the case when primes are compared to "superzooms", which sacrifice a degree of picture quality for their ability to cover a large range of focal lengths. (As an aside, let's forget that digital zooms exist, as they aren't comparable in quality to an optical zoom).

The second choice is between wide angle, standard and telephoto lenses. A standard, or "normal" lens produces a picture that looks more-or-less like what you would see normally. The perspective is what we're used to. A wide angle lens captures more than of the scene, but at the cost of making distances more pronounced. A telephoto lens zooms in on the scene, having a longer focal length than a standard lens, but it also shortens distances. As a guide, wide angle lenses are used for architecture and landscapes, and telephoto lens for birds and other subjects that are further away. The normal lens is often used for portraiture, although many photographers prefer a short telephoto, as it allows you to retain a comfortable distance without significantly changing the perspective.

The final thing to keep in mind (for now) is the speed of the lens. Lenses have a maximum aperture, and it is the aperture that limits how much light they let through. A lens that has a wide maximum aperture (for example, f2.8 or f1.4) is often said to be a "fast" lens, because it lets a lot of light through at once, allowing for faster shutter speeds and lower ISO settings. A slow lens uses a smaller maximum aperture, (such as f4 or f5.6), so it lets less light through the lens, and therefore requires slower shutter speeds or higher ISO settings. Faster lenses are better in low light conditions, at sporting events, or when you need to limit the blurring caused by camera shake (such as when zooming in on a distant object). In addition, fast lenses, when the aperture is wide open, only have a small "depth of field", which means you can be selective about what part of the photo is in focus - this is used to good effect by portrait photographers, who have the subject in focus but the background blurred and indistinguishable.

Options

All of this brings you to some options.

- Camera phones: these have a small sensor, generally a slow lens, and no zoom. Picture quality is comparitivly low, but with some of the smart phones you can get some nice software that will let you work with the image, improving the quality. The big advantage of camera hones is that you always have one with you, so for n unexpected snapshot they're not a bad choice - or rather, they're likely to be the only choice, and that's something.

- Consumer point-and-shoot cameras: The sensors on these are generally larger than on camera phones, but they are still very small. So the picture quality isn't going to equal a bigger camera. They generally come with a zoom lens, and they range between a 3x zoom and 12x or longer. However, the zooms are generally from "standard" to telephoto, so they often won't do wide angle shots. Thus if your interest is landscapes or architecture, shop around for a model with a wide angle lens. These cameras are great for convenience, and it is easy to always have one with you while providing for better picture quality than what you'll get from a camera phone. The main limitation, though, other than picture quality, is that they're limited in what they can do. As you improve in photography you will will find that they don't provide you with many options, such as control over depth of field, or the ability to support filters. Cheap cameras show up around the $100 mark, but expect to pay between $250 and $600.

- Professional point-and-shoot cameras: These are a fairly recent development. They come with a large sensor, up to the same size as a digital SLR, and a high quality lens, but the lens can't be changed. The result is SLR-quality or comparable photographs on a comparatively small camera. The problem is that they are fairly specialised: they aren't as flexible as either point-and-shoot or SLR cameras, but have a market with SLR photographers who need a smaller second camera and don't want to sacrifice image quality. Typically they sell for around the $1000 mark, and models include the Fuji FinePix X100 and the Panasonic DMC-GF1.

- SLR cameras: These provide a number of advantages. The large sensor provides good image quality, the ability to change the lens gives you a lot of flexibility, and when you look through the viewfinder you are also looking through the lens, so what you see is exactly what the camera will capture. The main disadvantages are size and weight: the mirror and prism needed to let you look through the lens adds a certain amount of bulk, as does the large sensor, and the lenses themselves are big and heavy. Consumer cameras start at around the $700 mark with one lens, and about $100 more for a twin lens pack. Serious enthusiast models are normally around $1500 with one lens, and new lenses can cost between $150 for something not very good, to over $30000 - typical prices for professional grade lenses, depending on focal length, quality and manufacturer, are between $600 and $2500. Choices include Canon, Nikon, Pentax and Sony. There are also a number of "Four Thirds" SLR cameras, which use a smaller sensor but are also physically smaller and can employ lighter and smaller lenses.

- MILC: Another relatively new development, these are based on the idea that with a digital camera you don't really need a viewfinder, and can use the screen instead. So they get rid of the viewfinder from an SLR, which means they can remove the mirror and prism, making the camera much smaller and lighter, while still retaining the ability to change lenses. (Hence MILC, Mirrorless Interchangable Lens Camera). They can also have a slightly smaller sensor than a typical SLR, so the picture quality isn't quite as good, (although it is close), but this allows the lenses and body to be be smaller. On the minus side, battery life can be a problem on some models, focusing can be slower than on an SLR, the range of lenses isn't as big as with most SLRs, and they're still not really pocket sized. That said, they're a very good choice if you don't like the size and weight of an SLR but want comparable image quality. Prices are normally between $800 and $1200, but there's a lot of new models coming out, and thus you can often get a good buy. Models include the Sony NEX, Panasonic Lumix DMC-G series, and the Olympus Pen EP series of cameras.

- Medium format digital cameras: Big, heavy, and expensive, but with a massive sensor. Image quality and pixel count can be huge, but nothing about them is cheap - prices start at around $10000 and rapidly go north from there. I mention them in the hope that someone reading this works for Pentax, Phase One, Hasslebald or another manufacturer and has the mad urge to send one my way for review. That would make me very happy.